1990's UK squat parties and loss of memory in maker culture

I wrote a slightly edited version of the following text in response to a discussion on the Nettime mailing list about the demise of corporate funding for the contemporary maker movement in what is now 2019. It’s the seed of an idea to discuss and enact the re-politicisation of making.

I was recently contacted by some old friends, some of whom I haven’t seen since I was 16 years old. These friends were part of London’s early squat party scene. This scene was distinct from ‘raves’ heard so much about in the mainstream press, where the mantra of “free party faceless techno” reacted against the notion of superstar DJ’s worshipped by dancers. Rather, DJ’s and sound-makers tended to be dimly lit, out of view, and amongst the dancers.

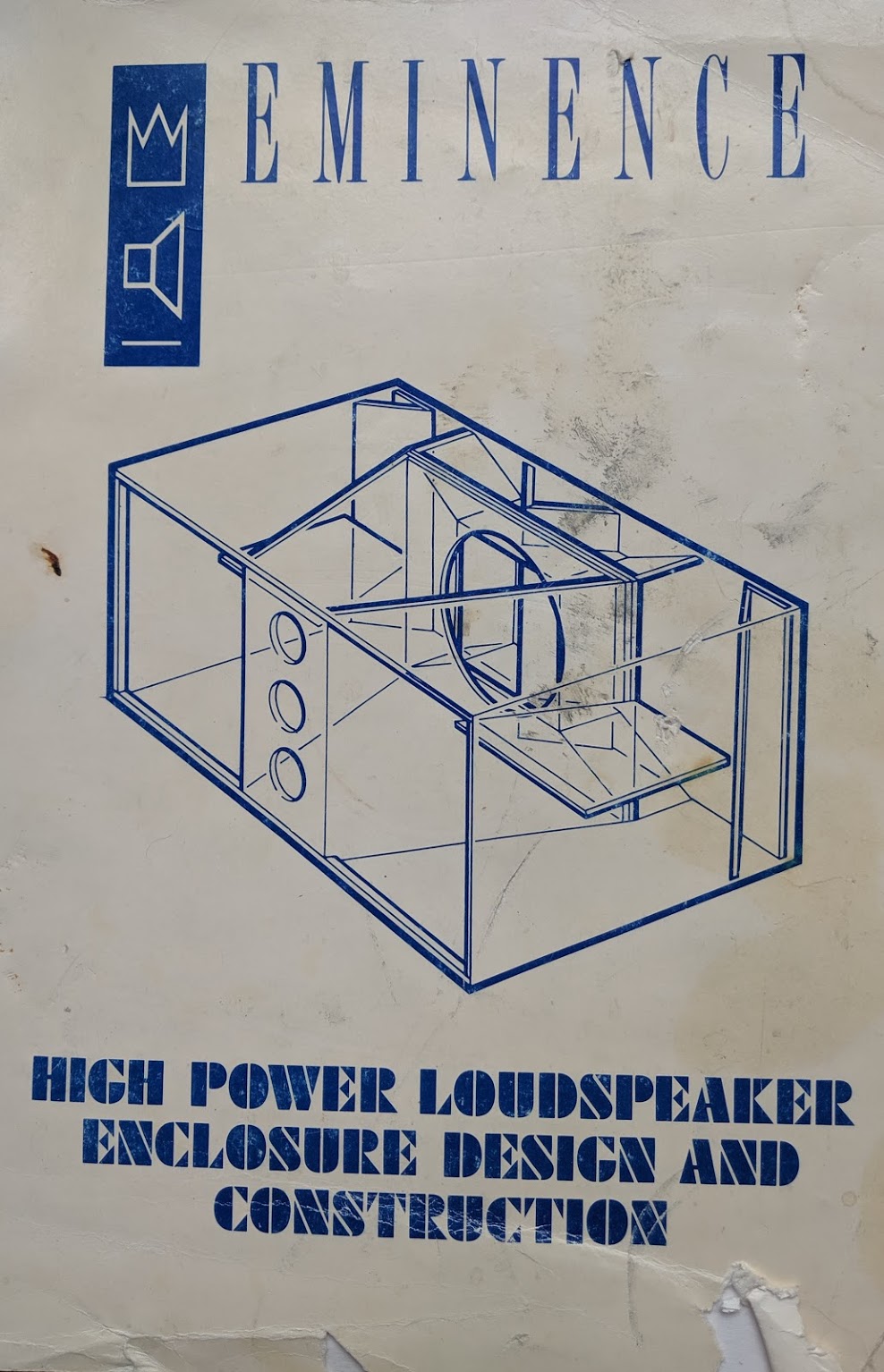

The free party scene was born out of punk, travellers, black sound system culture, a DIY ethos, and the drug ecstasy. My friends learnt how to build sound systems and their own sound-making equipment. I shared my soldering skills my grandpa taught me while sitting on his knee. My friends understood how to build things, operate generators, and drive large trucks. I got the sense that some gained that knowledge from the building trade, from their parents, or other worlds I did not inhabit. It was a different kind of knowledge than I had grown up with.

Those that didn’t understand how to build things or electronics helped move equipment, played records, painted banners, or simply dance all night with a smile. Some of the banner makers attended art school and seemed to be from middle-class backgrounds. Back then I often attempted to hide my class background, and rarely talked about class except to a few working class friends. However, the free party scene was an important meeting point of different academic, class, and (to a lesser extent) race backgrounds. Right or wrong, the ‘feeling’ was that anybody could afford to go to a free party and anybody could contribute. I think the range of people that attended forced people to think about difference (and struggle) even if they didn’t know it at the time.

I always found maker culture slightly strange when it gained prominence, it seems far removed from the maker culture of my predominantly working-class friends who put so much effort and gained so much expertise from their/our culture of making. Maker culture seemed to have lost its memory of earlier times. I’m reminded of a recent Keynote made Dr Johan Soderberg at a conference in the University of Nicosia in Cyprus which has a burgeoning maker/hacker culture in country dived by war. Johan quoted the socialist arts and crafts activist William Morris (1834-1896) “workers struggles continue under a different name” to discuss how struggles are re-named to become something else. He suggested swapping the word ‘worker’ with ‘hacker’ or ‘maker’ to highlight how re-naming can erase the collective memory of a struggle.

I think maker culture needs to re-connect with earlier struggles. The DIY culture of free parties connected to the squatter movement, housing struggles, road protests, women rights, globalism, and the Liverpool dockers. It politicised youngsters like me. The maker movement seems very distant from political struggles these days. Perhaps I am just starting to show my age, nostalgia for times past, or simply don’t get out enough because of my young kids. However, last night I attended a residents association meeting on a housing estate in north London to discuss homes that face demolition by mostly Labour Councils. I live on a housing estate that faces a similar fate. I undertake my research, making, theorising, and activism where I live because it connects with a tangible struggle. Let’s ask why maker spaces (or should we rename them?) don’t tend to exist in such environments and what they lose by remaining in their own enclave?

Tom Bowler (as I was known in the 1990s because I wore a Bowler Hat)